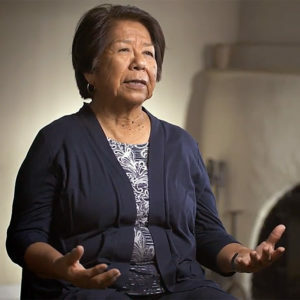

New Mexico & the Vietnam War: Portrait of a Generation

JANE CARSON

Through The Lens

Photos of and by Jane Carson

Jane's Story

(Note: this is the full transcript of the Carson interview, edited only for readability)

I joined the service because I come from a very patriotic family. My auntie's were in World War 2, in the Navy and all my brothers were either Navy or Army, so I just felt like I needed to join. My brothers didn't want me to join.

I was the youngest of four children so I had to see the world. This was my chance to do it, and I joined the Army Nurse Corps. I joined six months actually before nursing school and I was a private at $90 dollars staffing, and for a diploma graduate that was, like you know, pay dirt. I finished school in 1962 and I was supposed to go into the military on January of 63, but the Cuban crisis came along. They called us in early because they thought they'd send us down to Florida and that started my career. So when Khrushchev blinked, then we went to our normal duty stations.

"Patriotic means serving a nation where it needs to be served and unfortunately, war is where they need you the most."

Patriotic means serving a nation where it needs to be served and unfortunately, war is where they need you the most. I volunteered to go because the soldiers were there and that's where I needed to be. That's why I joined the army, to take care of the men and women in service. They were there, they were fighting, they needed my help. I figured I could hopefully help a little bit. 90% or 99% of the nurses volunteered.

When I went over to Vietnam, I flew into the wrong airport. They weren't used to getting women there, so I wandered around for three days because they didn't know what to do with me. I was assigned to the 312th Evacuation hospital. They asked me where I wanted to go, I said, “I don't know. I don’t know Vietnam or where the units are.” The process of where I was to be assigned, I left it up to them, because they knew where the needs were the greatest. So I said, “Assign me to wherever you need me most.”

The 312th was an evac hospital. We landed at the Chu Lai Air Base, a big air base there, and went over to the hospital and I got in my little bunk which was about an 8 by 10 room. We did have individual rooms and I had a fan in it and that’s it. It was very hot and humid. I remember that first night I thought, “Did I do the right thing?” I was very homesick by that time too.

The first morning I woke up, I went over to the mess hall. I was very homesick, and what did I find but eggs and grits for breakfast because, this was a reserve unit from Winston-Salem, North Carolina and they were all southern drawl and I felt right at home.

When I got to the hospital it was a shocker, because I’d never seen so much destruction from weapons. I mean nothing can prepare you for it but these men and women, civilians at the time, were just mangled from the high velocity weapons or missiles, or explosions.

Well, we took a tour of the hospital of course, so I saw casualties coming in to the emergency room. Sometimes their limbs, beside them, or not on the stretcher at all.

The operating room was going full-bore and you don't often have the chance to clean up in between cases so there's a lot of blood on the floor and the gurneys.

Then we went to the wards and we saw these beautiful young men, young being the opted word. We were all young, they were 17 or 18 and we were anywhere from 20 to…I think I was 25 and limbs missing, eyes missing, burns, horrible burns. It was quite a shocking experience because no matter how much training you had, nothing could prepare you for this, in this magnitude.

I do recall that I thought about the protests back here and I thought you know, “what are they protesting?” People got mixed up during the war and they blamed the soldiers to include the female soldiers, instead of the politicians who had created the whole thing.

I think everyone who went to Vietnam whether doctor, nurse, corpsman, you always wondered if you could be good enough for that next patient. You didn't know who was coming in or what their wounds were going to be and it was very difficult at times to be in the emergency room waiting for casualties to come in.

You just prayed that you could be strong enough for them, not only emotionally but that you would have the right knowledge that you needed, when they came in bleeding and you couldn't tell where they were bleeding from at first. You'd have to do an assessment and it was an incredible experience.

We did things as nurses that would never do here just because there weren’t enough physicians. You had to do a lot of the treatments and a lot of the assessments that the physicians would normally have to do here. We did just about everything over there, to keep the soldiers alive.

At the end of my first day they take me over to the officer's club and I'm sort of in shock or dazed. The first thing you think of is finding a way you can run away from what's happening, which is through alcohol or drugs. I wasn't much of a drinker or a drug user so I had to face reality right straight in the face. We went over to the officer's club and everybody was laughing and carrying on and I thought “what is this,” but that's the way you coped is through laughter and joking. It’s just I wasn't in a laughing mood that night. Eventually, I guess I was able to laugh a little bit more but it was too serious a deal for me.

I had trouble sleeping every night even though we worked 12-hour shifts, seven days a week. You never knew when a rocket was going to come in, they called it rocket alley. The 312th was about 90 miles southeast of Saigon and it was in between the America lst Marine Division and a Marine flight wing. They said that when the rockets were pointed toward them, they just happen to hit the hospital. I think they were aiming for the Red Cross because they were too often too close and too direct.

We got rockets maybe twice a week. That’s more than enough. Most of them would just knock the breath out of you. It's like the percussion would, even if it was way up at the hospital headquarters you would feel the whoomp. More than loudness, it was the percussion of it, you know that outward blast. No matter where you were it would be like somebody hit you in the stomach. I want to say heavy, because that's what it felt like. If you've ever been around a mortar you will never forget it actually knocking the wind out of you.

Pretty soon you didn't go to the bunkers. By the time the rocket hit, you know, we just stayed where we were. When you're in a ward, you had to cover your patients if they couldn't get underneath the bed or put them underneath their beds for protection. You didn't know, I mean you could hear at the last minute the whistle, but there was no warning system like there was for anything else. They just arrived.

There was a direct hit on the ward. It was early in the morning almost 6 o'clock before the lights went on and Sharon Lane, who was a First Lieutenant at the time, was down at the far end of the ward, just taking a breath of fresh air before they turned on the lights and started activity.

All the soldiers were sleeping, all the patients were sleeping and this rocket hit almost dead center in the Quonset huts. The Quonset huts have a connection in the center, so it's like an H and it hit in the center part of the H and destroyed the whole ward and killed Sharon from shrapnel. Shrapnel caught her in the throat and she bled out. The doctor came straight up from the emergency room but she had already bled out. It was always hard to lose any patient because you want to save them all, but to lose one of your own, right in the hospital compound. I mean it took the doc no more than three minutes to get up there, and we could not save her…could not save her.

I went back to Vietnam to dedicate a clinic to Sharon in Chu Lai. But we couldn't do it in Chu Lai, because the Communists had taken it over and they wouldn’t allow us to do it in Chu Lai, because that whole community was sort of off limits. So, we did it in the next village over and the beautiful thing about that, was meeting young people, and talking to them, and finding out the drive for freedom that they had. So even though people said, “Well, we should have never been in Vietnam, that was a lot of soldiers lost for nothing” that's not true. I saw it in their eyes and in talking with them, that one of these days Vietnam will be a free country, because of these youngsters growing up. When all the old guard die out, they'll be taking over the country. Vietnam is a beautiful country absolutely gorgeous if there hadn't been a war going on. But they have a bright history ahead of them I think.

One of the difficulties was that we didn't take any breaks, to grieve for those who had died. We just kept on chucking and kept on working. There's plenty more people to take care of, and they didn't stop coming, so we had a memorial service for her and then we went back to work. That has been a major problem for me, for years because we could not save her and then all the other thousands that came through that you couldn't save on top of that.

The incredible thing about patient care in Vietnam, was the helicopters. I think it was the first time they were really used to that extent on the battlefield. If a soldier could get back to us at the hospital they had a 98 percent chance of living no matter how wounded they were because, we had some incredible staff over there to do the jobs. But there were those who couldn't get back, who died on the battlefield, bled out before they could get them back.

It was a very disjointing tour, somehow we got a hold of a television. I had a roommate, [Robertajo “BJ” Kramer] a “hooch mate” they called it, and we got this little television set. It’s very hard to reconcile watching all the protests see them burning the flag and then going over to the ward and seeing all these men, primarily young men, their lives in shambles from either physical injuries or emotional injuries. I know that's one of the things that that took me so long to heal, and I’m still healing from that war. A lot of my friends protested war. They had no idea, they just saw and heard what was reported on the news. They were baby killers, they were all the bad things, they didn't show the good things that the soldier’s did. They did a lot of missions with orphanages and everything else in addition to the horrible job they had to do. They were totally misinformed. Instead of blaming the politicians, they blamed all of us who were over there, to include the women. We were all lumped in one pot as baby killers and not doing right by the Vietnamese. It was just very hard to put it all together. Finally it got so bad, I just had to turn the television off and concentrate on taking care of the soldiers.

Day in, day out we saw these casualties come in and sometimes those soldiers, they were so young they barely had peach fuzz. Many of them, I guess were drafted but a lot of them volunteered, for the same reason I did, because they thought they were helping their country. It was a time when you wanted to believe your government, and I bought hook line and sinker about the Communists taking over and the domino effect. That's why you have a lot of paranoid vets now. Truly, you learn to think hey, maybe that's not true when they send the soldiers to war.

There's an old quote from, I think its Robert E. Lee that said “War is hell.” So you do not want to go into it unless it's a very, very good reason and you want to make sure you have a strategy for it. So, I would just say that to the leaders anytime I met them.

I was head nurse at the 312th evac hospital, and because I was a captain which, I didn't have very much more experience but I had that captain insignia on my collar. So, I was supposed to know more I guess. I got four wards, two were Vietnamese, and two were enlisted soldiers. My job was just to support my staff and the soldiers on the ward. I was an overall supervisor. I did a lot of hands-on care too, because we were short-staffed so it was primarily supporting my staff and making sure they had what they needed and keeping them as happy as possible.

In addition to supporting my staff, of course, the whole reason we were over there, was to save lives and every minute of every day was focused towards that. We would start our day at about four o'clock in the morning, get ready, go to the mess hall, go to the hospital ward and have a report. And you knew, as soon as you hit that ward, that it was going to be nonstop all day. So, you tried to fortify yourself before you went in there. And just face all those young men. They were literally kids and we were their mother, their sister, their cousin, to them. We wrote letters home. They told us things, when they first came into the hospital that they probably never told another human being after leaving Vietnam. Horrible stories. We had to listen, and try to stay strong for them, but it would just rip your heart out sometimes, about what had been done to them because, Guerrilla warfare was horrible, it was bad.

One soldier told me about how they would scare them, by leaving bodies of their comrades, of their fellow soldiers, that were dead, and they had cut off everything that protruded, the nose, the ears, the penis, everything and they’d leave them there to rot. It would put mortal fear in them. I mean, you can imagine.

I don't think that soldier ever told another person about that. So we were definitely their confidantes and their letter writers and their “round eyes.” They always wanted to see round eyes and we would laugh about it, but it was a part of home that they missed. We might be hurting ourselves but we didn't show the soldiers.

We were dealing with high-velocity weapons, that had a small entry wound but then it would just blow out the back and they were horrible wounds. We dealt with these pointed sticks that they would put in the ground and camouflage so that they would step on them and it would go right through the boot and they would have feces on them, anything that would infect the foot and so they’d come in with horrible infections. The foot was almost rotted off, because they didn't get treated in time.

I had been promoted to supervisor on the night shift because nobody else wanted to do it, and I was a captain, remember. So, I was supposed to have a little bit more knowledge and experience.

So, this one night there was a huge push of mass casualties coming in, and I went to the emergency room to help them and I said, “what do you need,” and they said “go in the back and get some more supplies, bandages, and what have you.” I went back there and I don’t know why… I’ve never forgotten this young man on the gurney. He looked like he was sleeping. He had been pushed in the back, because they knew they couldn't save him. I didn't know what to do, other than to pick him up and hold him, you know, for his mother or his family back home, and his whole backside was just mush. To see him lying there so peacefully…he had probably just died when I went in there because he was still warm.

Those were some of the incredible things that happened. There's no way anything could prepare you for that. I've been through all the mass casualty courses but there's nothing that can prepare you for that. And why that particular young man, at that time, I do not know, but his face came back to me and still does, periodically in my dreams…because I couldn't understand…why him…Why?

We all had survivor guilt. Why any of those soldiers or why Sharon instead of us…instead of me?

It's pretty hard because sometimes, like the young man that was back in the supply room, you’d have to say, “give up on him” you know. His wounds were horrific, but still you didn't want to give up on any of them, so it was very hard to triage. I wanted save them all and most of us did, but you had to make some hard decisions. There's so many patients to be cared for, that we have to let someone go. Knowing full well, that they were going to die very soon, the only thing that I wanted to do is be there with them when they died. Some did not have anybody with them. I never wanted a soldier to die alone. Usually, we could be there with them, just to hold them, hold their hand. If you knew they had a favorite song, or hymn on that song, it was a personal mission, for me and I think for a lot of the nurses, that you be there with them, during the passing, that's the least we could do.

When a soldier was dying, I would try to cuddle them, because I'm a cuddler, my mother taught me to cuddle. I would just hold them close or hold their hand, if they were so injured I could not physically hug them. But some contact with them, to let them know that somebody's there by their side, cares for them and sort of hand them over to God.

The ones that died, normally, I did know their names because I'd talked to them, and I’d just be with them. I would hold them, and a lot of times, I would be the last person they would see alive. So that's why I wanted to be there for them and let them know that I was there with them, and they weren't dying alone.

To see a life pass out of these vibrant young, young men, it was an honor to be there, to be able to hold them. At the same time, it was very hard on your psyche, on your emotional state, because then you’d have to go to the next one. We had to stay strong for them, because they had such little hope. Can you imagine having all four limbs blown off? We were an evac hospital so we prepared them for evacuation and when we evacuated them from Vietnam, you wondered if you were doing them a favor. But then one day at the wall, at the Vietnam women's memorial, they would come up and tell you thank you for saving my life because…you really had no idea what happened to them after that and whether they were going to make it or not. Even those that didn't have the horrific physical wounds, it was the trauma they had been through and the emotional wounds, whether you knew they were going to make it.

One day on the ward, I was sitting behind the desk making out the schedule and the desks were very high, mainly to prevent shrapnel, in case you did get a good direct hit. So they were probably, I don’t know, five feet. I saw the screen door open and, I waited, thinking somebody would come up to the desk and I waited…but no one came. Finally my curiosity got the best of me, and I got up and looked around and here's this little weensy baby. She’s about, I don't know, not bigger than a grasshopper, but she had a candy bar in one hand and an ice cream in the other.

This happened after I got back from my mom's funeral. She was well when I left, and she died while I was over there. I didn't make it home for a few days but she essentially never woke up.

So here's this little baby, probably three years old, filthy dirty. She'd been on the convalescent ward and of course the medics were just teaching all sorts of choice words, letting her eat whatever she wanted to eat, and really spoiling her, as you would any child.

So she comes in the ward and her little shoes that they had stuffed her feet in, was all filled with pee-pee because they hadn't taught her to go to the bathroom. She had on panties which, over there they just let their kids run around without panties and they could wee, wee where ever they wanted to.

Mona, the chief nurse had named her Mona and…I had just gotten back from burying my mom…and this little waif comes in and I think, “Kid you need me and I sure need you.” Because I adored my mom and when she died so suddenly, I didn't care whether I lived or died, when I got back over there. So, Mona in a way saved my life.

When she came home with me, she had a splenectomy. She looked like she was about 16 months pregnant. Her little tummy was so large, if she had stayed over there she'd probably fallen playing or gotten hit in the stomach, and her spleen would have ruptured and she would have died. So the little rascal came home with me. I think the good Lord had a lot to do with that, because there had to be divine intervention, to make it all work.

The day I met her, I bathed her in a little bitty round basin. She hadn't been bathed that much obviously. She would not go in the shower or the bath tub. Then in the morning, somewhere we got a crib. We put it in the back of the ward. I'd go into work, take Mona with me, put her in the crib, let her finish sleeping. Then she’d get up and entertain the troops. She was wonderful for the troops because she reminded them of the children back home. Orphans were everyplace, and the GI’s would take care of a lot of orphans, and they would have fundraisers. Montagnards were treated like second-class citizens in Vietnam and Mona was a Montagnard.

Once I met this little tyke, she stole my heart and I said, “this is one life I've gotta save.” I did bring her along with me, but it was not easy. It took a lot of coordination and I was very thankful, that I was able to save one life directly. We saved a lot of lives, but this was one that I'd hoped would have a better future. Bringing Mona home… at least I was able to save one life, one child's life.

I flew into Treasure Island with Mona, but then I had to go to San Francisco to catch another flight. My family adopted her. My brother and sister-in-law and all their three boys and all their relatives, had a welcome home party. They were going to meet us, at the airport. They told us not to wear our uniforms, because people were not very nice to male or female soldiers. I did put on my uniform, and I carried her home, proudly because I was always a proud Army nurse. I just took my chances and I figured with this little kid on my shoulder surely no one would throw coffee or spit at me, and it was true. She got a royal welcome home from her adopting parents and it was a sight to behold. She finally had a family.

I couldn’t’t adopt her. I wanted to adopt her but that's during the time that women could not be in the military and have children, so it was not possible for me to adopt her. There'd been no question otherwise. So, I ended up being her aunty and she had a mom and dad, my oldest brother, so she had a good life.

It was ten years after the war, before anybody recognized PTSD in the men. Ten Years. And I knew what the men were going through, because I had PTSD. For women they said: “You know nurses shouldn't have PTSD because they weren't in combat.” We thought, “What's happening to me then,” because I mean I didn't know what PTSD was. I just knew I wasn't sleeping. I was having all sorts of intrusive thoughts, at one point. I almost killed myself. I tried, because I didn't know what was happening to me, and nobody recognized it in the women, and then finally they said, “Hey, well maybe you did see a few things.”

To be out there and not know what's happening to you, and you think you're going crazy, but you're not crazy. It’s just all these intrusive thoughts and not being able to sleep and sometimes, being in another reality. I mean the sound of a helicopter, even now we get helicopters from the base going over, and every time one goes by it startles me. Those types of sounds, I guess stay in your memory, because you never get over it. It is always there.

When I came back from Vietnam, I couldn't tell the military what was going on with me, because it wasn't recognized in women, until ten years after the men. I did like being in the military and if I had said, “Hey, I'm having all these crazy thoughts,” they would put me out of service, I'm sure. So I just dealt with it as best I could. I went to a civilian psychiatrist for a while, because if you went to a military psychiatrist, that was a death nail. Your promotions would stop and everything else.

But, these young men, they bore the brunt of it. They came in, they tried to heal themselves but then finally, finally, the military recognized that, “hey this is something more,” and it had been going forever. Since World War II. They just called it by a different name, “shell-shock.”

Thank goodness we finally recognized that you can't send people to war and expect them not to come back with some horrific wounds. Not just physical, but mental too. You don’t send a young man into the war, who has been taught never to kill anybody, and have them kill the enemy. You have to make the enemy out to something totally inhumane for them to pull that trigger, but once they do it totally changes them.

This is the first time in any battlefield where you had no front lines, because the battle was everywhere. It was the first time we had encountered guerrilla warfare, and so you were not safe no matter where you were. The women and men we would hire to come on base would often try to plant bombs in the barracks and other places. Not all of them, but you know it happened. There was no assurance that you were going to be safe. Well…I'm not saying that any war is safe, but with guerrilla warfare, you had snipers, you had people trying to booby trap the barracks, and the places you live, plus there were rockets coming in at pretty regular intervals. There is a feeling of insecurity at all times and so you had to work with this insecurity and at the same time be brave again for the soldiers. We didn't want to show that to them.

After Sharon died, I finally just stopped worrying about it, because I figured when it's your time to go, it's going to find you no matter what. She’s was as far as she could be from where that rocket came in, and yet a piece of shrapnel caught her in the throat, and killed her almost immediately.

When I came back home I knew there was something terribly wrong with me but no one recognized it. Even the Chief of the Corps said, “Nurses shouldn't have PTSD, because they weren’t in combat.” I suffered for so long on my own and then finally I realized in order to help myself, I had to help others. So, I got involved first in the Vietnam Women's Memorial and now I work with Paws to help animals.

You’re never the same again I mean there's no way you can be the same again. It’s very important to remember that when you go down into that valley, that you're always going to come up the other side. A couple of times I almost forgot that but thank the good Lord, I didn't and I'm here.

Animals saved my life. Literally, I've always loved animals but they certainly were part of my healing process because a dog or a cat or a horse or whatever it is, they have unconditional love. All they will require from you is that you feed them and pet them, take care of them, but other than that no matter what, no matter what your mood is, no matter how deep in despair you are they are there for you. That's why I chose animal work my second after the memorial. You're never the same, it never goes away but you know that there's something you can do in this world to make it better.

I don't sleep very well at night. I haven’t since Vietnam but, now that I'm retired I'm able to control my own schedule. So if I'm up half the night, then I will sleep a little later in the morning. I manage it that way. It's all the intrusive thoughts. When I do go to sleep, even sometimes when I don’t have them, it’s thinking I’m going to have them and not wanting to go there, you know, not wanting to feel those feelings again because there's times when you could be right back in Vietnam again. I'll wake up in a cold sweat and be with a patient on the ward. I still have a lot of nightmares. They’re not as frequent as before, but they are still there, and they're just as bad. Medication helps. The young man on the gurney comes back to me often. I’d like to say that maybe I was there when he died, but I think he probably had just died when I got to him. That young man still haunts me because it was such a dichotomy. Here’s a youngster on a gurney. He was a handsome black man, hardly able to shave and he looked like he was sleeping, but he was mortally wounded…and I didn't realize that until I picked him up a little bit to hold him, because you couldn't see any signs of wounds.

It's in your cells, and for a long time I did not accept that, and I thought that I was going to be the same Jane Carson that went into the war but, it doesn't happen that way. You have to adjust and you have to find your own passion to continue in this world, to be helpful and that's very important to me to be helpful. I wouldn’t have gone into nursing otherwise.

That's part of the nightmares I have. Some of them, there's others that are too gruesome to even talk about. It would be a wonderful thing if they found a way to cure it but there's no cure for it.

I’d just like to say that for all those people who thought Vietnam was a waste, it might have been at the time, we wasted a lot of ammunition and money but in the long run, I think we have, we have turned the tide, with the youngsters and there will be freedom in Vietnam. The lives lost were not in vain.

Some people still think that, “all those lives, fifty-seven thousand plus,” but they weren't. Their lives counted and Vietnam will be a free country one day.

Letters Home

Jane Carson's letters to her loved ones during the war

[masterslider id="18"]

POEM (untitled)

This is the poem that I wrote, one night after a big, big push and we got a lot of casualties in and it was a hellish night.

Warned of anguish on a hot July night,

a despair that was too overwhelming to recall.

Memories of a man, barely old enough to shave,

lay on the gurney at death's door way.

What can I do, what can I say,

to lessen the carnage on this hellish day?

Notes From War

Select pages from Jane Carson's diary during her service

[masterslider id="17"]

More Veteran Profiles Below | Back to New Mexico & Vietnam War Page